The Man Who Brought

" Ivy To Japan "

![[date-header-bg.gif]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiCYE3aiPBDWXi-w43FiVfcz7g1sWfQbZekRtSRUquWmWhw6Meh7CwiOGZ_rw2xTPWrmXx1hs9Xdb1po-nZeRoxKqVO1r2IGQRwZqVs3r6Xo7OZP77jnFHpZNSW9kWkvY6Eh_ugorJDgOKe/s1600/date-header-bg.gif)

In celebration of powerHouse Books’ publication of “Take Ivy” on August 31, Ivy-Style examines the life and career of Kensuke Ishizu, founder of Japanese clothing company VAN JACKET and the man who commissioned “Take Ivy.”

The article is by W. David Marx, who previously wrote on the Japanese youth cult the Miyuki-zoku. Marx himself has also brought Ivy to Japan: The Harvard grad currently resides in Tokyo.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of Ishizu in English.

* * *

Since the 1960s, Japan has been an important part of the story of the Ivy League Look, and during a few dark periods the island nation has played an important role in preventing the style from possible extinction.

Anyone interested in the Ivy-Japan connection will eventually encounter the name Kensuke Ishizu — perhaps on the inside cover of the newly released “Take Ivy.” Ishizu (1911-2005) was the founder of Japanese Ivy league-inspired clothing brand VAN (officially VAN JACKET), and easily the most important figure in post-war Japanese fashion before the rise of the international avant-garde designers Issey Miyake, Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto.

Background

Kensuke Ishizu was born into a prominent family in Okayama, a large city in Western Honshu. His father ran a paper wholesaler, which he was expected to eventually take over. At a young age, Ishizu developed a slightly unhealthy obsession with Western clothing. As a teenager, he requested his mother to send him to a specific school because he liked the cut of their uniforms. Biographer Takanori Hanafusa notes that this was highly unusual for the era. Until the 1950s, interest in fashion among Japanese men was generally taboo — a taboo Ishizu was central in breaking.

After relocating to Tokyo for university in the early 1930s, Ishizu used the full extent of his family’s wealth to pull a Gatsby. He drove around the city in his own car, bought expensive British-style bespoke suits, spent his nights at dance halls, and fooled around with girlfriends in the empty second-floors of noodle shops. Ishizu started living with his girlfriend in Tokyo, a younger girl he had known from Okayama, and once they got caught, they came home at 22 and were properly married.

After Japan’s imperialist expansion into China, Ishizu got away from his family for a while to move to Tianjin. Here Ishizu helped run a traditional Western gentleman’s store called Ogawa Yoko in the Japanese concession. In 1943, however, as the war started to turn against Japan, Ogawa Yoko’s Japanese employees decided to close the store and properly enlist. Ishizu joined the navy and took charge of a munitions factory. When the Chinese army eventually showed up to liberate the city, Ishizu was thrown into jail.

He was eventually released, and Ishizu befriended the American soldiers who later controlled the city. He became particularly chummy with a first lieutenant named O’Brien who had gone to Princeton. This would be Ishizu’s first time to hear about the Ivy League, but certainly not his last.

Ishizu Launches His Career

After repatriating, Ishizu went into Japan’s burgeoning fashion industry. Thanks to his experience running Tianjin’s premier men’s store, he became a cutting-edge producer for gentleman’s shops in western Japan. He eventually started his own store called Ishizu Shoten in Osaka, and as a leading expert on contemporary foreign style, Ishizu became an advisor to the post-war’s first serious men’s fashion magazine, Men’s Club.

He eventually founded his own brand VAN JACKET in 1951, with the name lifted from a left-wing tabloid of the time called Vanguard. At first the brand sold British suits and other traditional gentleman’s apparel, but in this era of nearly universal made-to-measure, VAN suffered from a lack of interest in off-the-rack suiting.

Ishizu needed a market for his ready-to-wear, and it was in this need that he made a crucial realization: Nobody made clothing for Japan’s enormous youth population. There had been a baby boom after the war, but companies had not yet tapped into the economic potential of this giant consumer segment. At the time, kids just wore their school uniforms or somewhat garish versions of their parents’ wardrobes. Moreover, there remained a delinquent stigma to the idea that youth would spend their money on clothing (Japan in the 1950s was still rebuilding its shattered economy, mind you). Ishizu became excited about this idea of outfitting the young, but the question was: What was the right style of clothing for them?

And here is where Ishizu remembered the Ivy League. Since the mid-’50s, Japanese men’s magazines had sometimes reported on American collegiate style and a few wealthy fashion leaders had adopted its tenets, but no one had ever attempted to actually manufacture Ivy items in Japan. And at this point, where the yen/dollar exchange rate was something like 360 ¥ to the dollar (it is currently around 89), importing from actual American outfitters was totally impossible.

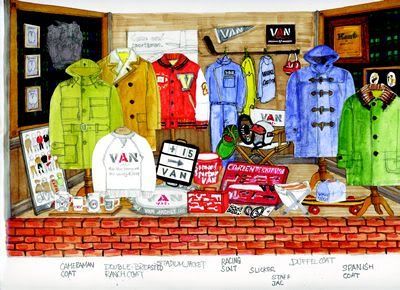

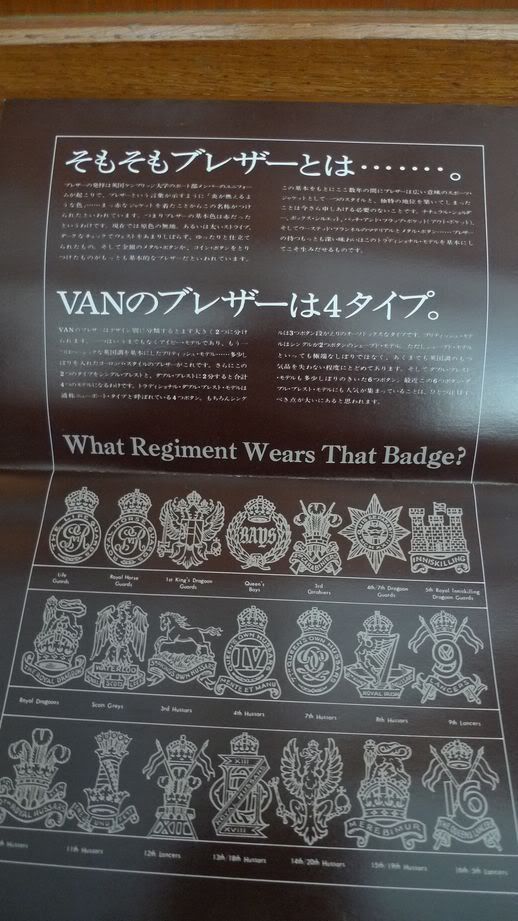

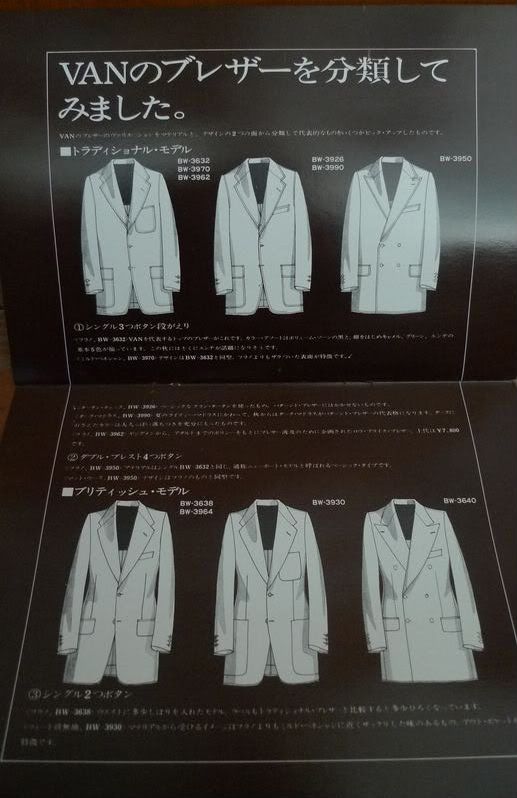

So VAN began to produce a full line of East Coast college style in the late 1950s, meant to be worn together in total coordination. This alone was innovative, as the industry was before divided into tie-makers, shirt-makers, pants-makers, jacket-makers and socks-makers. No one had ever attempted to make all items under a single brand. After studying Gant, Brooks Brothers and other classic brands, Ishizu was able to create extremely faithful recreations: oxford button-downs, high-water khakis, duffel coats, navy blazers with emblems, high-buttoning tweed hunting jackets, striped university scarves, and tons of madras.

VAN had a slow start with its relatively expensive Ivy gear, but in 1963, Men’s Club decided to retool the magazine to reach a younger audience. Ishizu came on board to make a big push for Ivy style to the youth — which he conveniently was also selling through VAN. The combination worked wonderfully, taking the specialist tailoring-focused title into mass market territory. And by 1964, Ivy League clothing became the cutting-edge fashion for Japanese middle-class kids. Paper shopping bags with the VAN logo became the coolest possible accessory for kids, to the point where some youth who could not afford to actually buy anything in the shop would just put VAN stickers on old rice bags to fake their patronage.

When epoch-making youth culture magazine Heibon Punch came on the scene in 1964, the editors also adopted Ivy league style as their signature look. This, of course, lead also to the “social problem” of the Miyuki-zoku. Despite that PR debacle, Ivy style was now the look for young Japanese men.

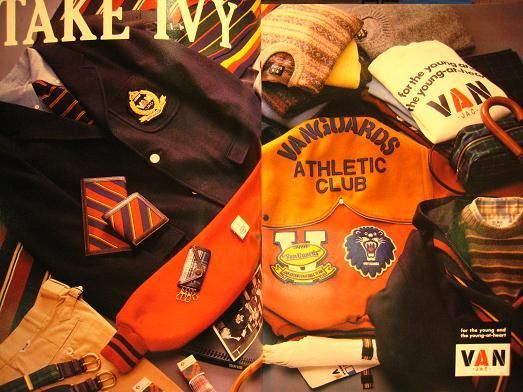

Success and Failure

VAN went on to become Japan’s leading brand in the 1960s, moving from Osaka to Tokyo’s upscale Aoyama in 1964. VAN not only advertised in the leading magazines of the day, but even sponsored a music show on TV called “VAN Music Break.” In 1965, Ishizu brought his team together with Men’s Club publisher Fujingahosha to create a photo book of actual Ivy League students. Eventually entitled “Take Ivy” after the Dave Brubeck song “Take Five,” the book served as a template that would inspire years and years of Men’s Club photo spreads of East Coast collegiate style.

Ishizu essentially acted as the godfather of men’s fashion during this decade, but interestingly, he was already a graying veteran during VAN’s peak. He was more like an accomplished bishop advising recent converts to his religion than the sexy style icons hyped in glossies today. And although he had a loyal following of young ambitious men, he was generally disliked amongst his contemporaries in the media and fashion industries. The apparel industry did not like him for changing the set rules on merchandising and avoiding planned obsolescence by going for a classic style like Ivy. The newspapers constantly trashed him for encouraging “juvenile delinquency.”

In the late 1970s, these critics were pleased to see VAN run into financial troubles. After the emergence of the counterculture, Japanese fashion inspiration moved towards laid-back West Coast American and “heavy duty” functional clothing. Ivy League style fell out of fashion among kids, and the diehard fans refused to bend it to match contemporary tastes. In 1978, VAN declared bankruptcy, and Ishizu faded into obscurity. Friends of Ishizu were concerned that Ishizu would take his own life in disgrace.

These fears were unfounded, however, and Ishizu’s almost immediately staged an impressive comeback. Thanks to the early ’80s preppy trend in the US, and the Japanese publication of “The Official Preppy Handbook,” there grew a new interest in East Coast clothing among Japanese youth. To the chagrin of the courts and prior vendors, VAN returned to business in 1981, and in 1982 fashion magazine Hot Dog Press dedicated an entire issue to Ishizu as the grandfather of American style in Japan, an issue that outsold rival magazine Popeye for the first time. And even in this era of a strong yen and therefore affordable imports from Brooks Brothers, Ralph Lauren and Jeffrey Banks, VAN was the standard-bearer for the Japanese Ivy look.

Or maybe not. VAN went bankrupt again in 1984. In 2000, trading company Itochu licensed the brand for a series of cheap GMS merchandise. The current VAN line — a mid-priced nostalgia line for baby boomer dads who couldn’t afford it back in the day — is based on a completely different license with no connection to the Ishizu family. Ishizu’s son Shosuke, who worked with his father throughout the brand’s history, now runs a site called the Button Down Club. Tellingly, there is no link to the current VAN brand on the site.

Legacy of Ishizu

The most striking detail about Ishizu is that his individual actions alone brought Ivy league style to Japan. Almost every famous Japanese Ivy-related project — “Take Ivy,” Men’s Club, etc. — has his fingerprints on it. Perhaps Ivy fashion would have come to Japan on its own in the deep Japanese dedication to American fashions, but it was he who had the resources to actually put affordable versions in the Japanese market right in the nascent years of the consumer market. And Ishizu also had the leadership in the industry to show youth how the style was a legitimate one worth buying into, something that remains a prerequisite for success in Japan.

Although he played up his chance meeting of First Lieutenant O’Brien in Tianjin as the initial spark, Ishizu clearly had a natural sympathy to Ivy style’s central Old Money tenets. Like Haruki Murakami, Shintaro Ishihara and Haruomi Hosono, most of Japan’s post-war cultural pioneers came from elite backgrounds, and their upbringing let them arbitrage their heightened understanding of Western values in a culture obsessed with the latest in foreign products. Kensuke Ishizu was one of the few people who could have “translated” Ivy League fashion to the Japanese, as he had lived as close of an existence to upper-crust New England families as was possible in 1930s Japan.

VAN’s success also made the fashion business a serious destination for Japan’s elite youth. Once shunned as unserious, this growing field was then able to recruit top talent from the best universities. Former Seibu Department Stores president Seiichi Mizuno, an elite Keio University graduate, told me in a 2008 interview that he originally joined Seibu solely because they had a VAN store before any of the other department stores.

When Ishizu died in 2005 at the age of 94, he had no funeral and donated his body to science. With the large number of biographies and anthologies of his lifestyle philosophy, however, Ishizu needed no public memorial. His legacy lives on with every Japanese person who wears an oxford cloth button-down. — W. DAVID MARX

W. David Marx is a writer living in Tokyo whose work has appeared in GQ, Brutus, Nylon, and Best Music Writing 2009, among other publications. He is currently Chief Editor of web journal Néojaponisme and formerly an editor of Tokion and the Harvard Lampoon.

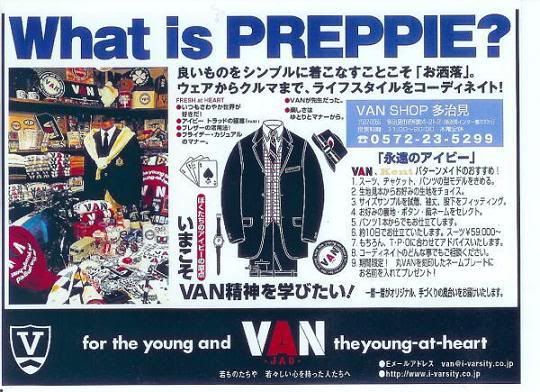

Some vintage VAN ads:

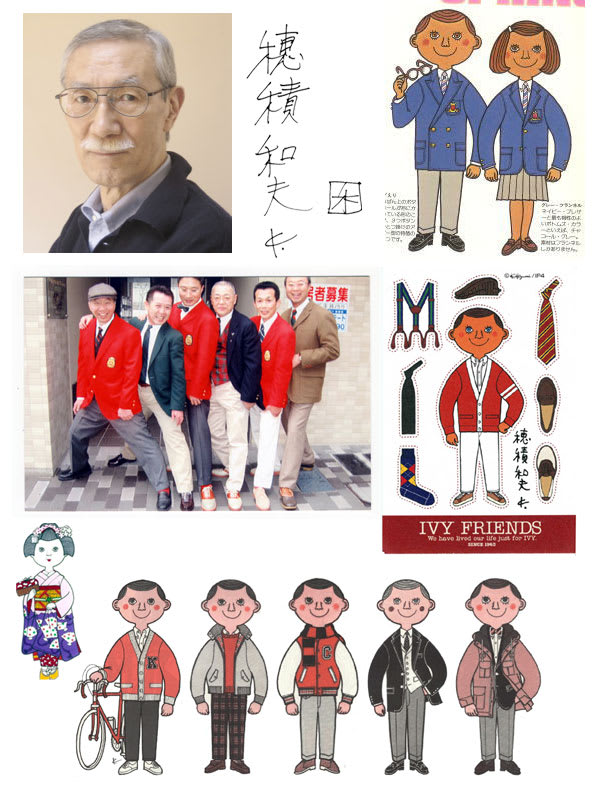

A couple of those caricatures that Japanese Trads seem to like:

...and in toy form:

VAN art

...and artist

Pavement ads?

Regimental stripe sport shirts from VAN's Fall/Winter 2009 collection

VAN ad

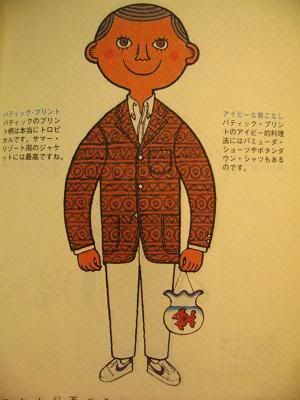

A little Trad Psychedelia in one of those Japanese caricatures. (For some reason, wearing Nike Cortez running shoes...)

And another one.

And a third.

Also, in coffee cup form.

VAN's "Fireman Coat"

Disconcerting Trad action figures.

Beach art?

Origami

VAN madras tennis hat!

A good question.

A good point.

If Brooks Brothers can do it...

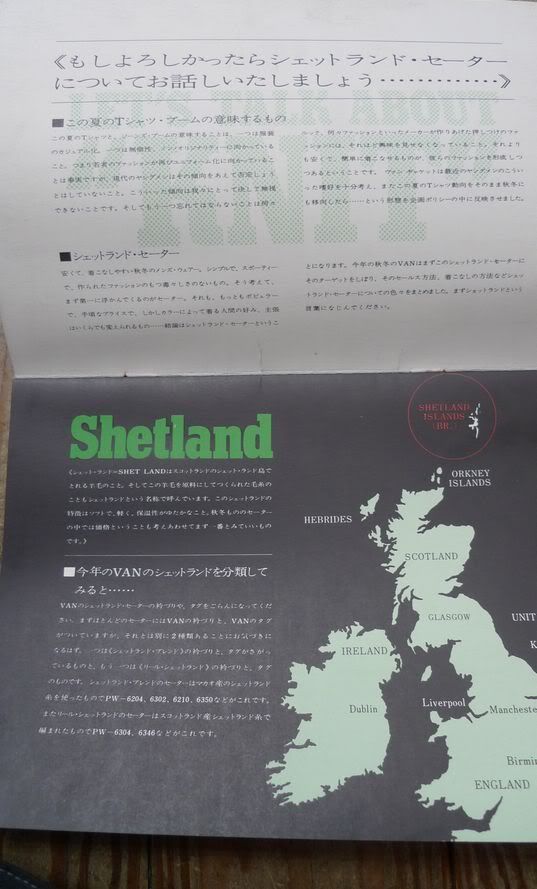

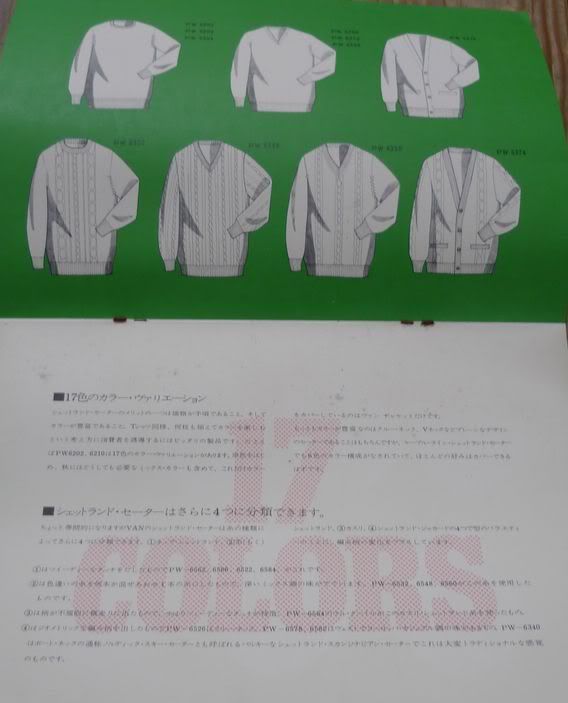

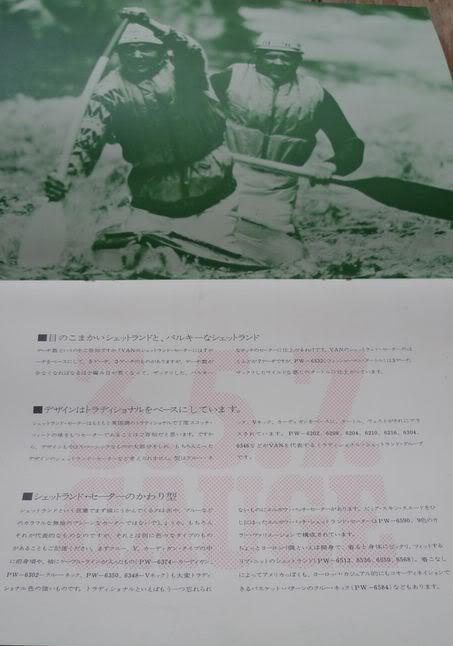

Also, "Let's Talk About 'Knit'", courtesy of Japanese blogger bhhkh906:

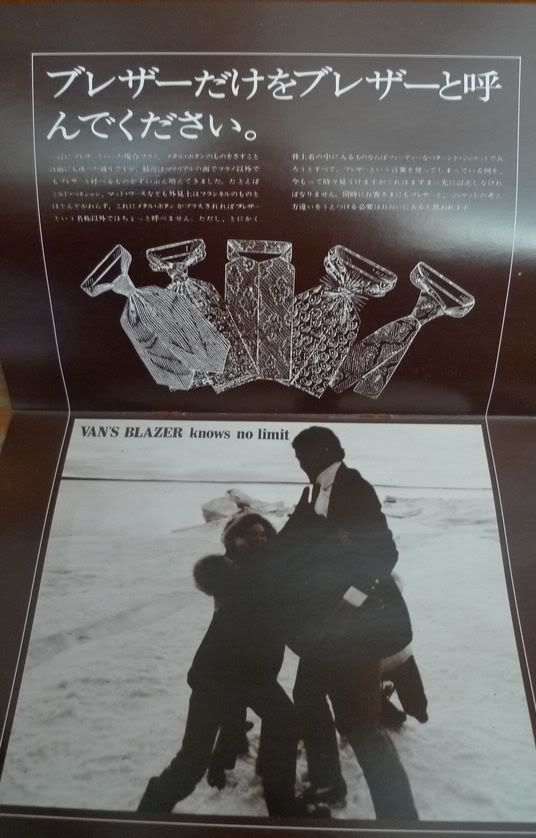

And while we're on the subject, "Let's Talk About 'Blazer'":

.........................................................................................

"for the young and the young-at-heart"

No comments:

Post a Comment